Quotes from Former Slaves

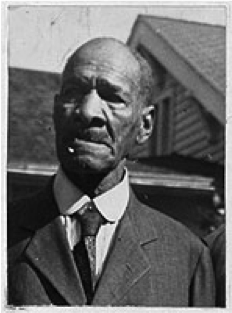

“Could be called a ‘conductor’ on the underground railway, only we didn’t call it that then. I din’t know as we called it anything—we just knew there was a lot of slaves always a-wantin’ to get free, and I had to help ‘em.”

—Arnold Gragston, age 97, Jacksonville, Florida

Photo credit: {{PD-US}} – published before 1923 and public domain in the US

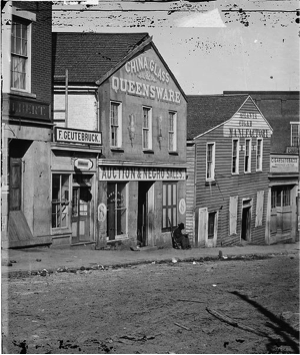

“Talkin’ ‘bout somethin’ awful, you should have been dere. De slave owners was shoutin’ and sellin’ chillen to one man and de mamma and pappy to ‘nother. De slaves cries and takes on somethin’ awful. If a woman had lots of chillen she was sold for mo’, cause it a sign she a good breeder.”

—Millie Williams, age unknown, Texas

“I remember when they put ‘em on the block to sell ‘em. The ones ‘tween 18 and 30 always bring the most money. The auctioneer he stand off at a distances and cry ‘em off as they stand on the block. I can hear his voice as long as I live.”

—W. L. Bost, age 87, Asheville, North Carolina

“Course dey cry; you think dey not cry when they was sold lak cattle? I could tell you ‘bout it all day, but even den you couldn’t guess de awfulness of it.”

—Delia Garlic, age 100, Montgomery, Alabama

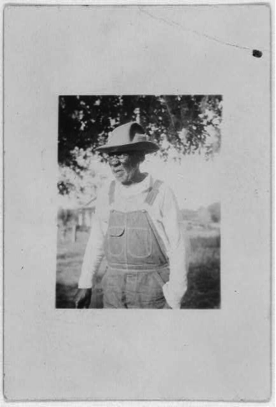

"And he call me and told me to run down in the field and tell Peter to turn the people loose, that the Yankee coming. And so I run down in the field and whooped and holler.”

—Wallace Quarterman, age 87

Photo credit: Lomax Collection (LOT 7414)

“My marser’s name was Isaac Hunter. Him an’ de missus bofe hellcats . . . Marser daid now an’ I ain’ plannin’ on meetin’ him in heaven neither.”

—Armaci Adams, age 93, Huntersville, Virginia

“If I had my life to live over I would die fighting rather than be a slave again. I want no man’s yoke on my shoulders no more.”

—Robert Falls, age 97, Knoxville, Tennessee

“Bells and horns! Bells for dis and horns for dat! All we knowed was go and come by de bells and horns!”

—Charley Williams, around 95 years old, Monroe, Louisiana

Photo credit: Library of Congress Manuscript Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA

“They sold my mother, sister, and brother to old man Askew, a slave speculator, and they were shipped to the Mississippi bottoms in a boxcar. I never heard from my mother any more. I never seed my brother again, but my sister come back to Charlotte. She come to see me. She married and lived there till she died.”

—Patsy Mitchner, age 84, Raleigh, North Carolina

Photo credit: George N. BarnardM

“If I thought, had any idea, that I’d ever be a slave again, I’d take a gun an’ jus’ end it all right away. Because you’re nothing but a dog. You’re not a thing but a dog.”

—Fountain Hughes, age 101, Baltimore, Maryland

“There wasn’t no reason to run up North. All we had to do was but walk South, and we’d be free as soon as we crossed the Rio Grande. In Mexico you could be free. They didn’t care what color you was, black, white, yellow, or blue. Hundreds of slaves did go to Mexico and got on all right.”

—Felix Haywood, age 92, San Antonio, Texas

“I sure has had a hard life. Jes wok an’ wok an wok. I nebbah know nothin’ but wok . . . No’m I nebbah knowed whut it wah t’ rest. I jes wok all de time f’om mawnin’ till late at night . . . Lawdy, honey, yo’ cain’t know what a time I had. All cold n’ hungry. No’m, I aint tellin’ no lies. It de gospel truf. It sho is.”

—Sarah Gudger, age 121, Asheville, North Carolina

Photo credit: Library of Congress Manuscript Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA

“I think the time will soon be when people won’t be looked on as regards to whether you are black or white, but all on the same equality. I may not live to see it but it is on the way. Many don’t believe it, but I know it.”

—Delicia Patterson, age 92, Boonville, Missouri

“Massa used to give ‘em [runaways] somethin’ to eat when dey hide dere. I saw dat place operated, though it wasn’t knowed by dat den, but long time after I finds out dey call it part of de “underground railroad.” Dey was stops like dat all de way up to de North.”

—Lorenzo Ezell, age 87, Spartanburg County, South Carolina

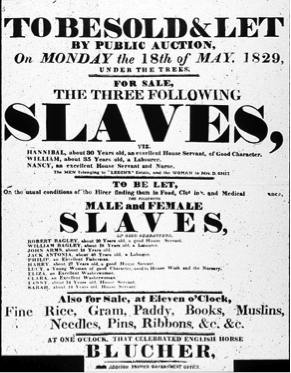

Photo credit: John Addison, Printer, Government Office, East India Company, St. Helena

“Slavery was a bad thing, and freedom, of the kind we got, with nothing to live on, was bad. Two snakes full of poison. One lying with his head pointing north, the other with his head pointing south. Their names was slavery and freedom.”

—Patsy Mitchner, age 84, Raleigh, North Carolina

“We wuz glad ter be free, an’ lemmie tell yo’, we shore cussed ole martser out ‘fore we left dar; den we comed ter Raleigh. “

—Charlie Crump, age unknown, North Carolina

“Then one day along come a Friday and that a unlucky star day and I playin’ round de house and marster Williams come up and say, “Delis, will you ‘low Jim walk down the street with me?” My mammy say, “All right, Jim, you be a good boy,” and dat de las’ time I ever heard her speak, or ever see her. We walks down whar de houses grows close together and pretty soon comes to de slave market. I ain’t seed it ‘fore, but when marster Williams says, “Git up on de block,” I got a funny feelin’, and I knows what has happened.”

—James Green, around 98 years old, born Petersburg, Virginia

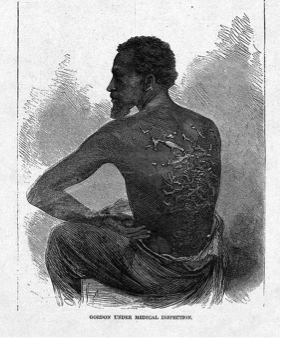

“I lays in de bunk two days, gittin’ over dat whippin’, gittin’ over it in de body but not de heart. No suh, I has dat in de heart till dis day.”

—Andy Anderson, age unknown, Fort Worth, Texas

“Lots of old slaves closes the door before they tell the truth about their days of slavery.”

—Martin Jackson, around 91 years old, Victoria County, Texas

“We lib in uh one room house in de slave quarter dere on de white folks plantation. My Gawd, sleep right dere on de floor . . . Fed us outer big bowl uv pot licker wid plenty corn bread en fried meat en dat ‘bout aw we e’er eat.”

—Hector Godbold, age 87, Marion County, South Carolina

“It was the law that if a white man was caught trying to educate a Negro slave, he was liable to prosecution entailing a fine of fifty dollars and a jail sentence. . . Our ignorance was the greatest hold the South had on us. We knew we could run away, but what then?”

—John W. Fields, age unknown, Lafayette, Indiana

Photo credit: Library of Congress Manuscript Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA

“De happies’ time o’ my life wuz when Cap’n Tipton, a Yankee s