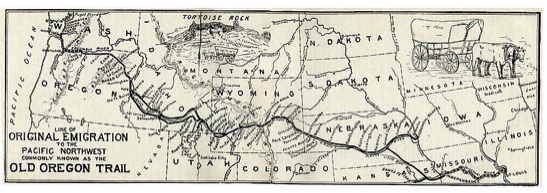

Oregon Trail Facts:

The Oregon Trail traverses six states: Missouri, Kansas, Nebraska, Wyoming, Idaho, and Oregon.

Photo credit: Courtesy of the University of Texas Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin

The average overland journey took between 4 ½ to 5 months in a covered wagon. Today it can be driven in 4 1/2 days or flown over in 4 hours.

In 1842, the first emigrant to die from a firearm accident on the Oregon Trail was ironically named John Shotwell. He made the fatal mistake of getting his gun out of his wagon muzzle first.

Between 1841, when overland wagon travel began, and 1866 an estimated 500,000 emigrants headed west over the trail.

Photo credit: {{PD-US}} – published before 1923 and public domain in the US

After crossing the Rocky Mountains and entering present-day Idaho, the emigrants in the early 1840’s considered themselves officially in Oregon Territory, which extended west from the Continental Divide.

Wagon trains lumbered over the ground at a speed between 1 and 2 miles per hour. The emigrants walked between 10 and 15 miles per day, taking just over one week to go 100 miles.

Once the emigrants left the plains and began their ascent through the mountains, the trail became littered with treasured heirlooms and keepsakes deemed too heavy to transport any further. This may be one reason that the officer’s quarters at the military forts established along the trail in later years seemed to be especially well appointed.

Four times as many emigrants traveled west in the 1850s than had in the 1840s, but the earlier excursions were found to be more worthy of newspaper coverage, so more records are available for the earlier journeys.

There were more fatalities from the accidental discharge of guns than from confrontations with Indians.

The army sent out soldiers on the Oregon Trail as early as 1845 to retrieve individuals who were attempting to flee from their debts.

Up till 1849 a hired trail guide was deemed to be essential to the success of a wagon train. After the trails became more defined and trail traffic became heavier guides were no longer seen as a necessity.

Commencement of an overland journey usually occurred during a five-week window from the last week of April through the end of May. The starting date depended upon when the grasses on the plains were deemed high enough to sustain the beasts of burden during the trip.

Photo credit: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA

When letters were carried east after the emigrants had settled in their new homes, emigrants often included 10 cents to have their names and addresses printed in border town newspapers so that their loved ones back home could locate them.

Mass migration over the Oregon Trail by wagon was only made possible after a wide gap through the Rocky Mountains, called South Pass, was identified in 1824.

The greatest percentage of overlanders came from Missouri, Illinois, Iowa, and Indiana, and 60 percent were farmers. Immigrants came from all over the globe to travel west on the trail.

The Oregon, California, and Mormon Pioneer Trails followed the general path of the Platte River for 450 miles. Between Fort Laramie, Wyoming, and Fort Bridger, Wyoming, the trails were virtually one in the same.

Astronauts are said to be able to make out two manmade objects from space: the Great Wall of China and the traces of the Oregon Trail.

An estimated 34,000 to 45,000 lives were lost along the Oregon Trail. That’s between 17 to 22 lives per mile.

The nation’s busiest highway, Interstate 80, follows the same path as the Oregon Trail along part of its distance, as did the Transcontinental Railroad when it was completed.

Photo credit: Chris Light at en.wikipedia

Just 20 percent of the historic ruts created by the steady wear of wagon wheels along the Oregon Trail remain identifiable today after nearly one and a half centuries of disuse.

Outfitting a family of four including wagon, animals, and provisions cost between $500 and $1,000. In today’s dollars that would be between $7,986 and $15,972. Emigrants often had to save one- to three-years wages to afford the trip.

There are some 200 known graves, most unmarked, along the Oregon Trail. To protect the graves of their loved ones from being disinterred the dead were often buried directly under the path of the trail. Wagons passing over would help to obliterate any sign so the graves could not be detected.

Photo credit: National Register of Historic Places listings in Hood River County, Oregon

It is estimated that 1 out of every 250 emigrants kept diaries or journals while heading west. In later years some emigrants wrote their reminisces, adding to the history of overland travel.

The first third of the Oregon Trail was geographically the easiest, but it was also the most disease-ridden. The last third of the trail was the most physically challenging due to the terrain.

Between the years of 1841 to 1869, the heyday of the Oregon Trail, there were nine U.S. presidents.

Photo credit: Randy C. Bunne; Great Circle Photographics

The completion of the Transcontinental Railroad in 1869 is said to have brought an end to the wagon-train era. However, as late as 1895 covered wagons could still be seen heading west.

By 1899 all Native American tribes in Oregon were on government-designated reservations.

A few emigrants en route had quite the surprise when they climbed up trees to view what they thought were eagle nests. It was the custom of some Indian tribes to bury their dead up in scaffolds in the trees so that they would be closer to the spirit world.

Oregon came into the Union as the thirty-third state on February 14, 1859. Today, it is the ninth largest state in area.

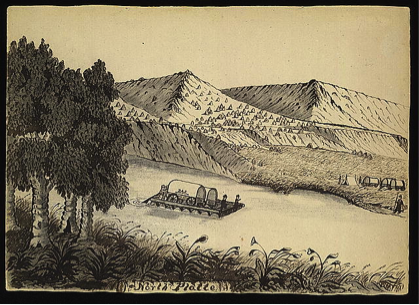

Some historians believe the end of the Oregon Trail was at The Dalles, a place of rocky rapids along the Columbia River. However, most emigrants were headed for the Willamette Valley. Until the Barlow Road offered a bypass they still had to either raft down the Columbia River or scale the Cascade Mountains to reach their final destination.

The first place in which the Oregon Trail split was at the “Parting of the Ways” in south central Wyoming. The left fork headed to Utah and California and the right fork was the Sublette Cutoff, which headed to Oregon.

The second place where the Oregon Trail split was just past Soda Springs, Idaho. The left fork took the Hudspeth Cutoff heading to California and the right fork continued on to Oregon.

The wheels of the covered wagons were anchored to stakes driven into the ground and attached with ox chains so the wagons would not blow over in wind and rainstorms.

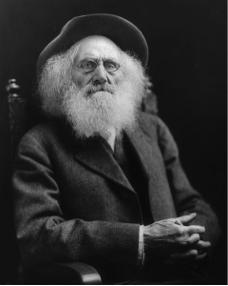

In 1978, Congress designated the 2,000-mile trail as the National Historic Oregon Trail due largely to the efforts of pioneer Ezra Meeker who worked tirelessly to preserve the Oregon Trail.

Photo credit: PD-US "No known restrictions on publication."